Accessibility

Introduction

Accessibility on the web is essential for an inclusive and equitable society. As more of our social and work lives move to the online world, it becomes even more important for people with disabilities to be able to participate in all online interactions without barriers. Just as building architects can create or omit accessibility features such as wheelchair ramps, web developers can help or hinder the assistive technology users rely on.

When thinking about users with disabilities, we should remember that their user journeys are often the same—they just use different tools. These popular tools include but are not limited to: screen readers, screen magnifiers, browser or text size zooming, and voice controls.

Often, improving the accessibility of your site has benefits for everyone. While we typically think of people with disabilities as people with a permanent disability, anybody can have a temporary or situational disability. For example, someone might be permanently blind, have a temporary eye infection, or, situationally, be outside under a glaring sun. All of these might explain why someone is unable to see their screen. Everyone has situational disabilities, and so improving the accessibility of your web page will improve the experience of all users in any situation.

The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) advise on how to make a website accessible. These guidelines were used as the basis for our analysis. However, in many cases it is difficult to programmatically analyze the accessibility of a website. For instance, the web platform provides several ways of achieving similar functional results, but the underlying code powering them may be completely different. Therefore, our analysis is just an approximation of overall web accessibility.

We’ve split up our most interesting insights into four categories: ease of reading, media on the web, ease of page navigation, and compatibility with assistive technologies.

No significant difference in accessibility was found between desktop and mobile during testing. As a result, all of our presented metrics are the result of our desktop analysis unless otherwise stated.

Ease of reading

The primary goal of a web page is to deliver content users want to engage with. This content might be a video or an assortment of images, but many times, it’s simply the text on the page. It’s extremely important that our textual content is legible to our readers. If visitors can’t read a web page, they can’t engage with it, which ends up with them leaving. In this section we’ll look at three areas in which sites struggled.

Color contrast

There are many cases where visitors to your site may not be able see it perfectly. Visitors may be colorblind and unable to distinguish between the font and background color (1 in every 12 men and 1 in 200 women of European descent). Perhaps they’re simply reading while the sun is out and creating tons of glare on their screen—significantly impairing their vision. Or maybe they’ve just grown older and their eyes can’t distinguish colors as well as they used to.

In order to make sure your website is readable under these conditions, making sure your text has sufficient color contrast with its background is critical. It is also important to consider what contrasts will be shown when the colors are converted to grayscale.

#FCA469. The right column says Recommended and the brown background color is written as #BD5B0E. The top box in each column has an brown background with white text #FFFFFF and the bottom box has a gray background with white text #FFFFFF. The grayscale equivalents are #B8B8B8 and #707070 respectively. Courtesy of LookZookOnly 22.04% of sites gave all of their text sufficient color contrast. Or in other words: 4 out of every 5 sites have text which easily blends into the background, making it unreadable.

Zooming and scaling pages

Using a legible font size and target size helps users read and interact with your website. But even websites perfectly following all of these guidelines can’t meet the specific needs of each visitor. This is why device features like pinch-to-zoom and scaling are so important: they allow users to tweak your pages so their needs are met. Or in the case of particularly inaccessible sites using tiny fonts and buttons, it gives users the chance to even use the site.

There are rare cases when disabling scaling is acceptable, like when the page in question is a web-based game using touch controls. If left enabled in this case, players’ phones will zoom in and out every time the player taps twice on the game, ironically making it inaccessible.

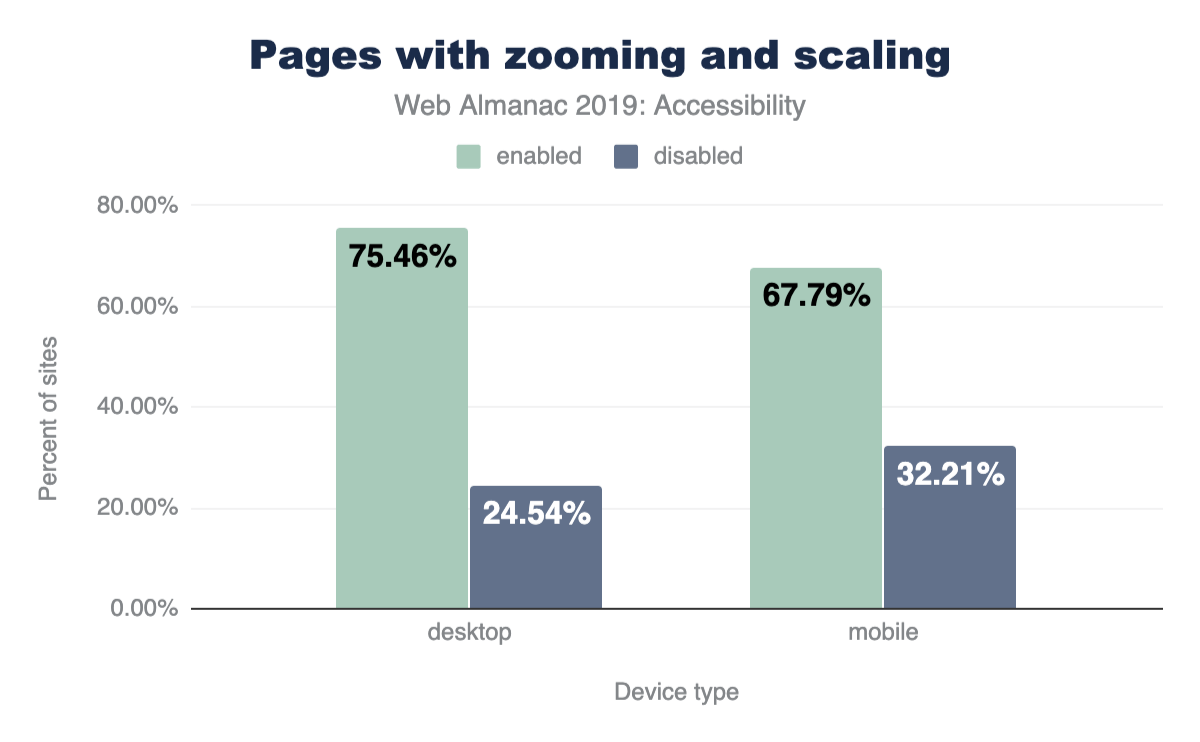

Because of this, developers are given the ability to disable this feature by setting one of the following two properties in the meta viewport tag:

-

user-scalableset to0orno -

maximum-scaleset to1,1.0, etc

Sadly, developers have misused this so much that almost one out of every three sites on mobile (32.21%) disable this feature, and Apple (as of iOS 10) no longer allows web-developers to disable zooming. Mobile Safari simply ignores the tag. All sites, no matter what, can be zoomed and scaled on newer iOS devices.

Language identification

The web is full of wondrous amounts of content. However, there’s a catch: over 1,000 different languages exist in the world, and the content you’re looking for may not be written in one you are fluent in. In recent years, we’ve made great strides in translation technologies and you probably have used one of them on the web (e.g., Google translate).

In order to facilitate this feature, the translation engines need to know what language your pages are written in. This is done by using the lang attribute. Without this, computers must guess what language your page is written in. As you might imagine, this leads to many errors, especially when pages use multiple languages (e.g., your page navigation is in English, but the post content is in Japanese).

This problem is even more pronounced on text-to-speech assistive technologies like screen readers, where if no language has been specified, they tend to read the text in the default user language.

Of the pages analyzed, 26.13% do not specify a language with the lang attribute. This leaves over a quarter of pages susceptible to all of the problems described above. The good news? Of sites using the lang attribute, they specify a valid language code correctly 99.68% of the time.

Distracting content

Some users, such as those with cognitive disabilities, have difficulties concentrating on the same task for long periods of time. These users don’t want to deal with pages that include lots of motion and animations, especially when these effects are purely cosmetic and not related to the task at hand. At a minimum, these users need a way to turn all distracting animations off.

Unfortunately, our findings indicate that infinitely looping animations are quite common on the web, with 21.04% of pages using them through infinite CSS animations or <marquee> and <blink> elements.

It is interesting to note however, that the bulk of this problem appears to be a few popular third-party stylesheets which include infinitely looping CSS animations by default. We were unable to determine how many pages actually used these animation styles.

Media on the web

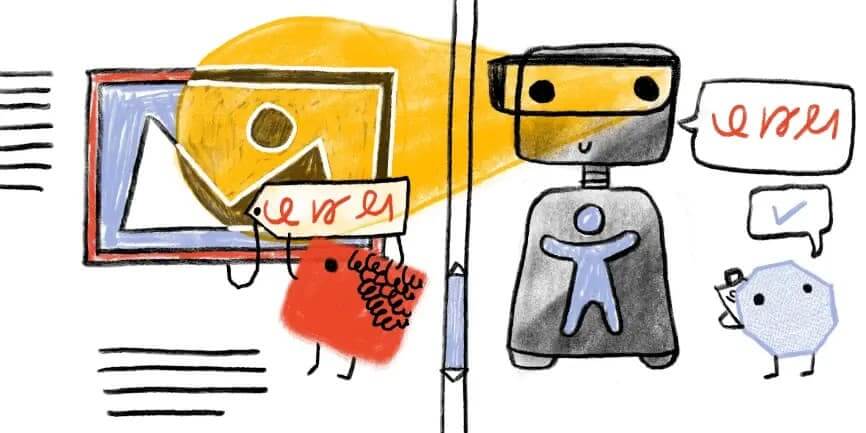

Alternative text on images

Images are an essential part of the web experience. They can tell powerful stories, grab attention, and elicit emotion. But not everyone can see these images that we rely on to tell parts of our stories. Thankfully, in 1995, HTML 2.0 provided a solution to this problem: the alt attribute. The alt attribute provides web developers with the capability of adding a textual description to the images we use, so that when someone is unable to see our images (or the images are unable to load), they can read the alt text for a description. The alt text fills them in on the part of the story they would have otherwise missed.

Even though alt attributes have been around for 25 years, 49.91% of pages still fail to provide alt attributes for some of their images, and 8.68% of pages never use them at all.

Captions for audio and video

Just as images are powerful storytellers, so too are audio and video in grabbing attention and expressing ideas. When audio and video content is not captioned, users who cannot hear this content miss out on large portions of the web. One of the most common things we hear from users who are Deaf or hard of hearing is the need to include captions for all audio and video content.

Of sites using <audio> or <video> elements, only 0.54% provide captions (as measured by those that include the <track> element). Note that some websites have custom solutions for providing video and audio captions to users. We were unable to detect these and thus the true percentage of sites utilizing captions is slightly higher.

Ease of page navigation

When you open the menu in a restaurant, the first thing you probably do is read all of the section headers: appetizers, salads, main course, and dessert. This allows you to scan a menu for all of the options and jump quickly to the dishes most interesting to you. Similarly, when a visitor opens a web page, their goal is to find the information they are most interested in—the reason they came to the page in the first place. In order to help users find their desired content as fast as possible (and prevent them from hitting the back button), we try to separate the contents of our pages into several visually distinct sections, for example: a site header for navigation, various headings in our articles so users can quickly scan them, a footer for other extraneous resources, and more.

While this is exceptionally important, we need to take care to mark up our pages so our visitors’ computers can perceive these distinct sections as well. Why? While most readers use a mouse to navigate pages, many others rely on keyboards and screen readers. These technologies rely heavily on how well their computers understand your page.

Headings

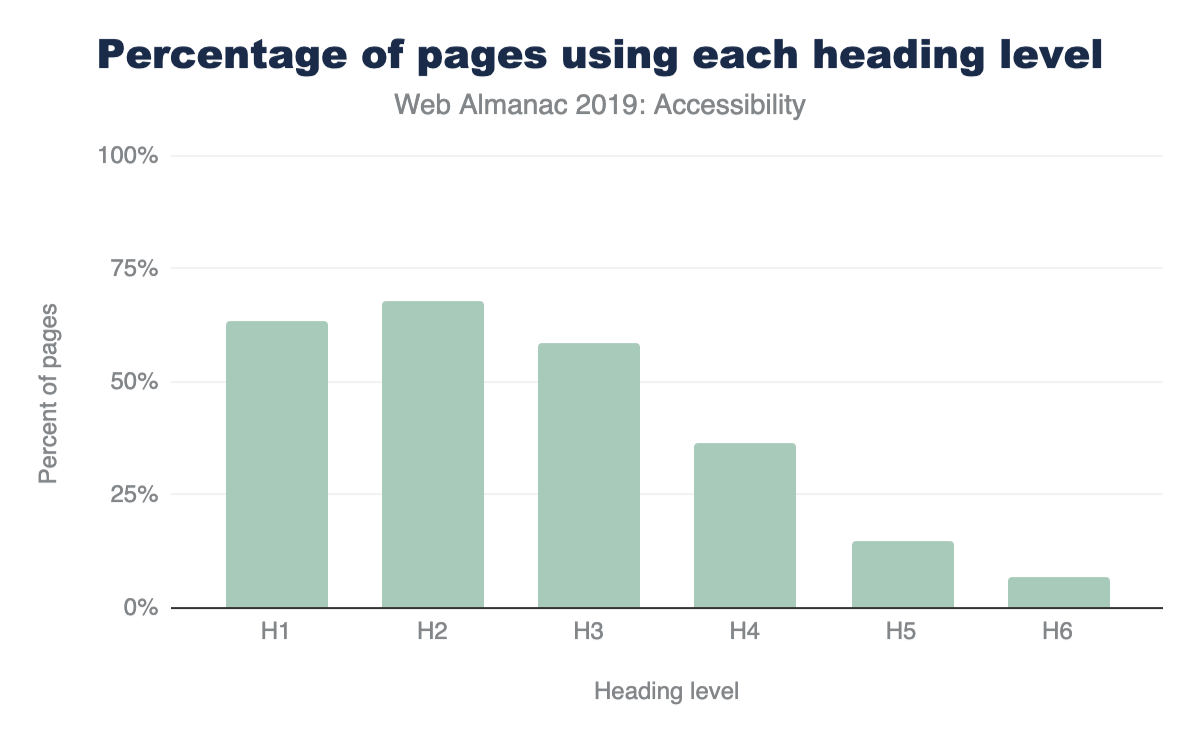

Headings are not only helpful visually, but to screen readers as well. They allow screen readers to quickly jump from section to section and help indicate where one section ends and another begins.

In order to avoid confusing screen reader users, make sure you never skip a heading level. For example, don’t go straight from an H1 to an H3, skipping the H2. Why is this a big deal? Because this is an unexpected change that will cause a screen reader user to think they’ve missed a piece of content. This might cause them to start looking all over for what they may have missed, even if there isn’t anything missing. Plus, you’ll help all of your readers by keeping a more consistent design.

With that being said, here are our results:

- 89.36% of pages use headings in some fashion. Awesome.

- 38.6% of pages do skip heading levels.

- Strangely, H2s are found on more sites than H1s.

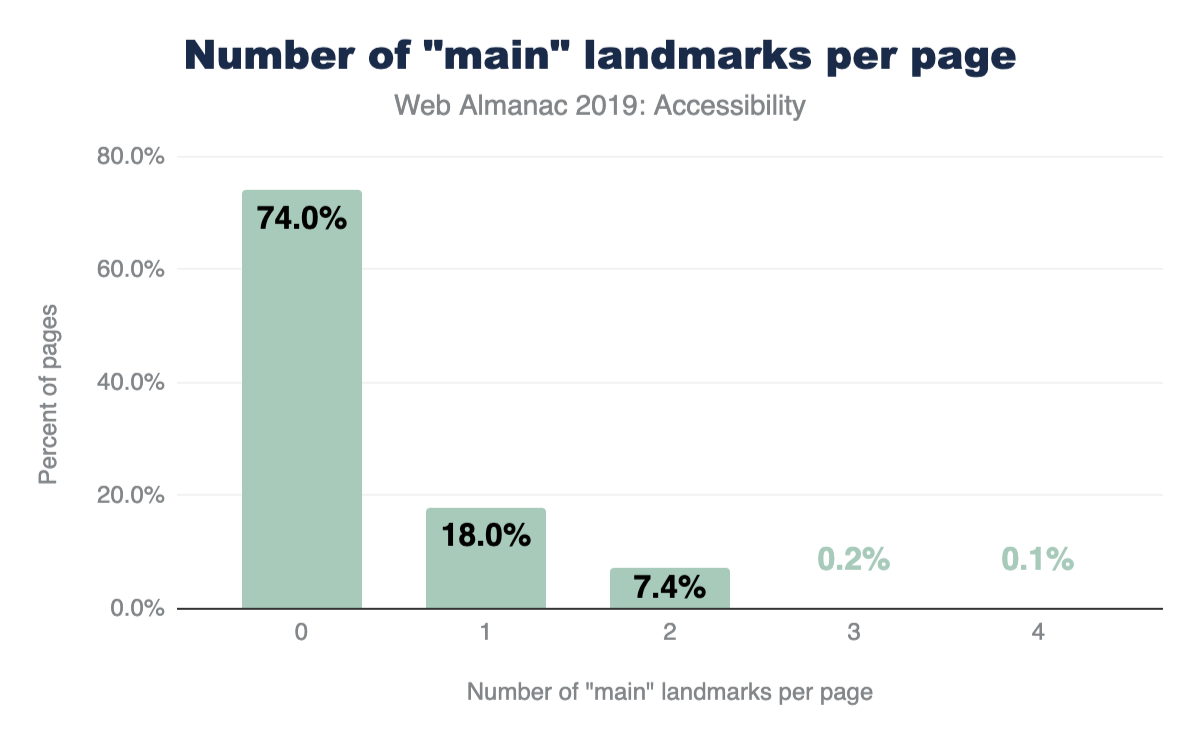

Main landmark

A main landmark indicates to screen readers where the main content of a web page starts so users can jump right to it. Without this, screen reader users have to manually skip over your navigation every single time they go to a new page within your site. Obviously, this is rather frustrating.

We found only one in every four pages (26.03%) include a main landmark. And surprisingly, 8.06% of pages erroneously contained more than one main landmark, leaving these users guessing which landmark contains the actual main content.

HTML section elements

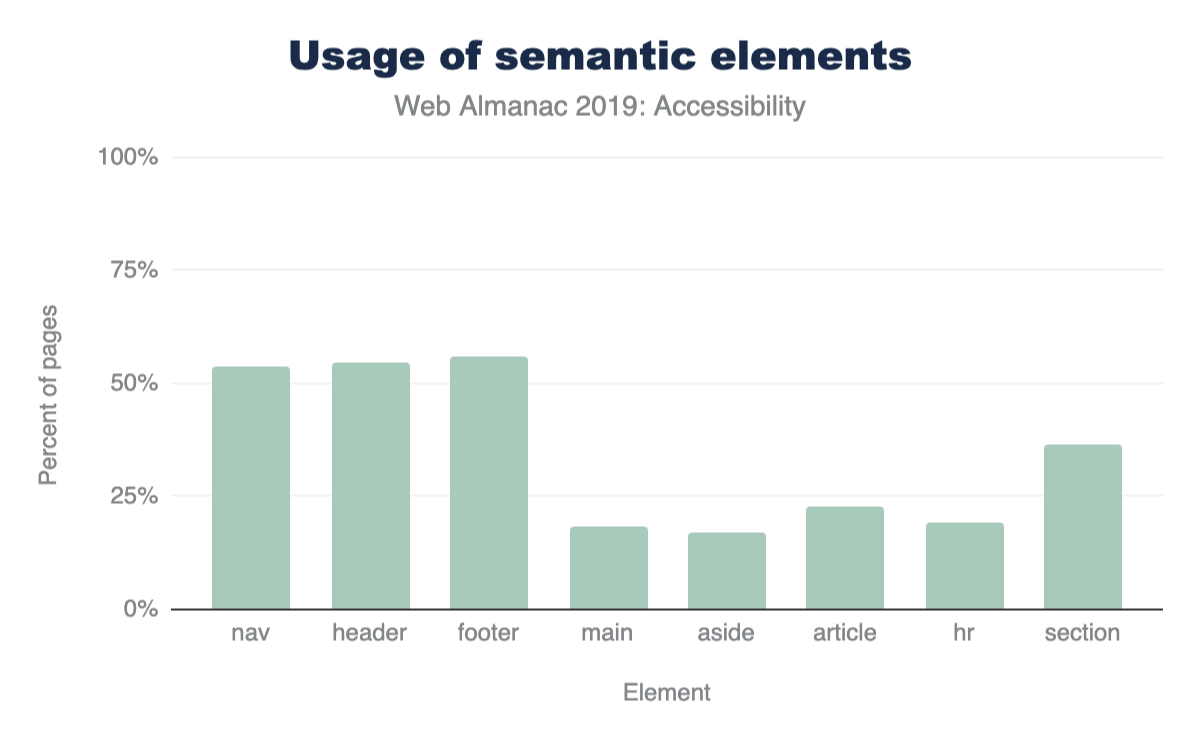

Since HTML5 was released in 2008, and made the official standard in 2014, there are many HTML elements to aid computers and screen readers in understanding our page layout and structure.

Elements like <header>, <footer>, <navigation>, and <main> indicate where specific types of content live and allow users to quickly jump around your page. These are being used widely across the web, with most of them being used on over 50% of pages (<main> being the outlier).

Others like <article>, <hr>, and <aside> aid readers in understanding a page’s main content. For example, <article> says where one article ends and another begins. These elements are not used nearly as much, with each sitting at around 20% usage. Not all of these belong on every web page, so this isn’t necessarily an alarming statistic.

All of these elements are primarily designed for accessibility support and have no visual effect, which means you can safely replace existing elements with them and suffer no unintended consequences.

Other HTML elements used for navigation

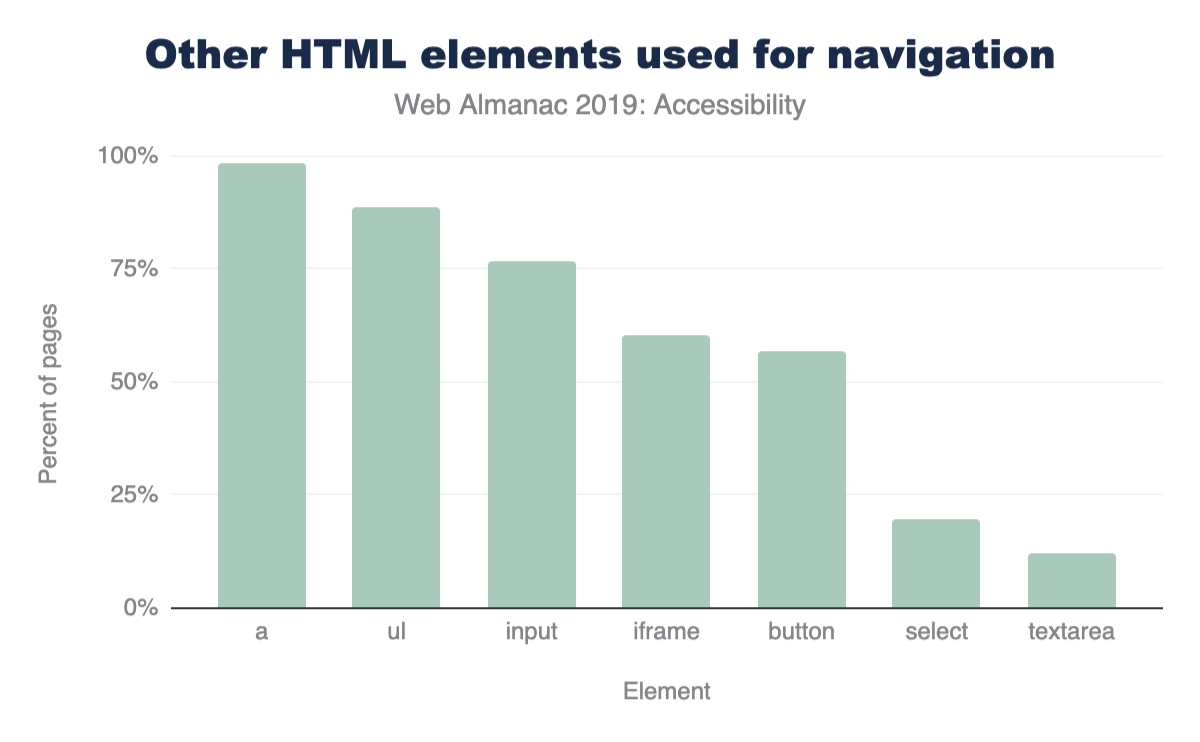

Many popular screen readers also allow users to navigate by quickly jumping through links, lists, list items, iframes, and form fields like edit fields, buttons, and list boxes. Figure 9.6 details how often we saw pages using these elements.

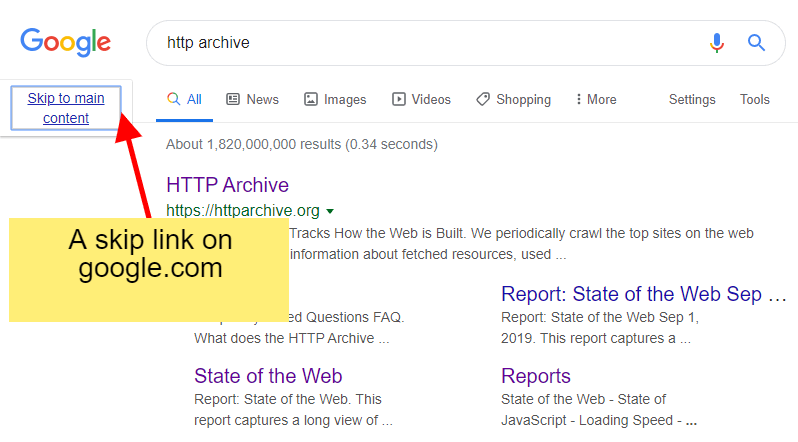

Skip Links

A skip link is a link placed at the top of a page which allows screen readers or keyboard-only users to jump straight to the main content. It effectively “skips” over all navigational links and menus at the top of the page. Skip links are especially useful to keyboard users who don’t use a screen reader, as these users don’t usually have access to other modes of quick navigation (like landmarks and headings). 14.19% of the pages in our sample were found to have skip links.

If you’d like to see a skip link in action for yourself, you can! Just do a quick Google search and hit tab as soon as you land on the search result pages. You’ll be greeted with a previously hidden link just like the one in Figure 9.7.

In fact you don’t need to even leave this site as we use them here too!

It’s hard to accurately determine what a skip link is when analyzing sites. For this analysis, if we found an anchor link (href=#heading1) within the first 3 links on the page, we defined this as a page with a skip link. So 14.19% is a strict upper bound.

Shortcuts

Shortcut keys set via the aria-keyshortcuts or accesskey attributes can be used in one of two ways:

Activating an element on the page, like a link or button.

Giving a certain element on the page focus. For example, shifting focus to a certain input on the page, allowing a user to then start typing into it.

Adoption of aria-keyshortcuts was almost absent from our sample, with it only being used on 159 sites out of over 4 million analyzed. The accesskey attribute was used more frequently, being found on 2.47% of web pages (1.74% on mobile). We believe the higher usage of shortcuts on desktop is due to developers expecting mobile sites to only be accessed via a touch screen and not a keyboard.

What is especially surprising here is 15.56% of mobile and 13.03% of desktop sites which use shortcut keys assign the same shortcut to multiple different elements. This means browsers have to guess which element should own this shortcut key.

Tables

Tables are one of the primary ways we organize and express large amounts of data. Many assistive technologies like screen readers and switches (which may be used by users with motor disabilities) might have special features allowing them to navigate this tabular data more efficiently.

Headings

Depending on the way a particular table is structured, the use of table headers makes it easier to read across columns or rows without losing context on what data that particular column or row refers to. Having to navigate a table lacking in header rows or columns is a subpar experience for a screen reader user. This is because it’s hard for a screen reader user to keep track of their place in a table absent of headers, especially when the table is quite large.

To mark up table headers, simply use the <th> tag (instead of <td>), or either of the ARIA columnheader or rowheader roles. Only 24.5% of pages with tables were found to markup their tables with either of these methods. So the three quarters of pages choosing to include tables without headers are creating serious challenges for screen reader users.

Using <th> and <td> was by far the most commonly used method for marking up table headers. The use of columnheader and rowheader roles was almost non-existent with only 677 total sites using them (0.058%).

Captions

Table captions via the <caption> element are helpful in providing more context for readers of all kinds. A caption can prepare a reader to take in the information your table is sharing, and it can be especially useful for people who may get distracted or interrupted easily. They are also useful for people who may lose their place within a large table, such as a screen reader user or someone with a learning or intellectual disability. The easier you can make it for readers to understand what they’re analyzing, the better.

Despite this, only 4.32% of pages with tables provide captions.

Compatibility with assistive technologies

The use of ARIA

One of the most popular and widely used specifications for accessibility on the web is the Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) standard. This standard offers a large array of additional HTML attributes to help convey the purpose behind visual elements (i.e., their semantic meaning), and what kinds of actions they’re capable of.

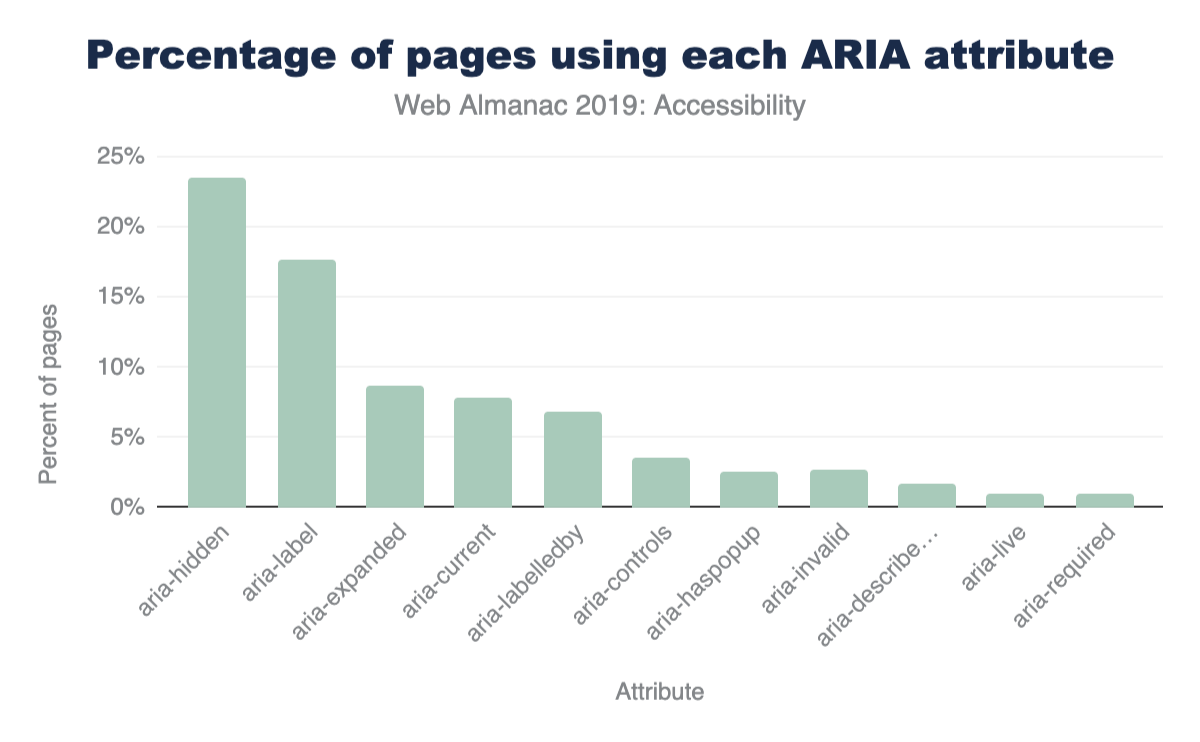

Using ARIA correctly and appropriately can be challenging. For example, of pages making use of ARIA attributes, we found 12.31% have invalid values assigned to their attributes. This is problematic because any mistake in the use of an ARIA attribute has no visual effect on the page. Some of these errors can be detected by using an automated validation tool, but generally they require hands-on use of real assistive software (like a screen reader). This section will examine how ARIA is used on the web, and specifically which parts of the standard are most prevalent.

aria-hidden: 23.46%, aria-label: 17.67%, aria-expanded: 8.68%, aria-current: 7.76%, aria-labelledby: 6.85%, aria-controls: 3.56%, aria-haspopup: 2.62%, aria-invalid: 2.68%, aria-describedby: 1.69%, aria-live: 1.04%, aria-required: 1%

The role attribute

The “role” attribute is the most important attribute in the entire ARIA specification. It’s used to inform the browser what the purpose of a given HTML element is (i.e., the semantic meaning). For example, a <div> element, visually styled as a button using CSS, should be given the ARIA role of button.

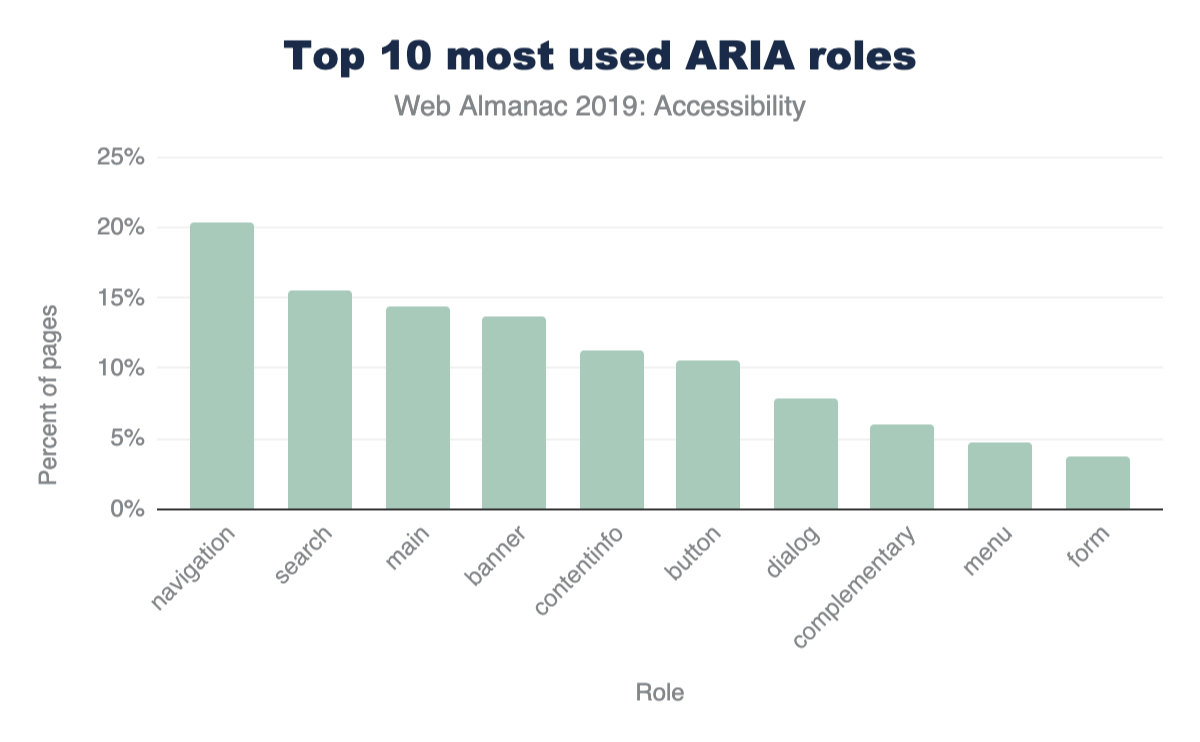

Currently, 46.91% of pages use at least one ARIA role attribute. In Figure 9.9 below, we’ve compiled a list of the top ten most widely used ARIA role values.

Looking at the results in Figure 9.9, we found two interesting insights: updating UI frameworks may have a profound impact on accessibility across the web, and the impressive number of sites attempting to make dialogs accessible.

Updating UI frameworks could be the way forward for accessibility across the web

The top 5 roles, all appearing on 11% of pages or more, are landmark roles. These are used to aid navigation, not to describe the functionality of a widget, such as a combo box. This is a surprising result because the main motivator behind the development of ARIA was to give web developers the capability to describe the functionality of widgets made of generic HTML elements (like a <div>).

We suspect that some of the most popular web UI frameworks include navigation roles in their templates. This would explain the prevalence of landmark attributes. If this theory is correct, updating popular UI frameworks to include more accessibility support may have a huge impact on the accessibility of the web.

Another result pointing towards this conclusion is the fact that more “advanced” but equally important ARIA attributes don’t appear to be used at all. Such attributes cannot easily be deployed through a UI framework because they might need to be customized based on the structure and the visual appearance of every site individually. For example, we found that the posinset and setsize attributes were only used on 0.01% of pages. These attributes convey to a screen reader user how many items are in a list or menu and which item is currently selected. So, if a visually impaired user is trying to navigate through a menu, they might hear index announcements like: “Home, 1 of 5”, “Products, 2 of 5”, “Downloads, 3 of 5”, etc.

Many sites attempt to make dialogs accessible

The relative popularity of the dialog role stands out because making dialogs accessible for screen reader users is very challenging. It is therefore exciting to see around 8% of the analyzed pages stepping up to the challenge. Again, we suspect this might be due to the use of some UI frameworks.

Labels on interactive elements

The most common way that a user interacts with a website is through its controls, such as links or buttons to navigate the website. However, many times screen reader users are unable to tell what action a control will perform once activated. Often the reason this confusion occurs is due to the lack of a textual label. For example, a button displaying a left-pointing arrow icon to signify it’s the “Back” button, but containing no actual text.

Only about a quarter (24.39%) of pages that use buttons or links include textual labels with these controls. If a control is not labeled, a screen reader user might read something generic, such as the word “button” instead of a meaningful word like “Search”.

Buttons and links are almost always included in the tab order and thus have extremely high visibility. Navigating through a website using the tab key is one of the primary ways through which users who use only the keyboard explore your website. So a user is sure to encounter your unlabeled buttons and links if they are moving through your website using the tab key.

Accessibility of Form Controls

Filling out forms is a task many of us do every single day. Whether we’re shopping, booking travel, or applying for a job, forms are the main way users share information with web pages. Because of this, ensuring your forms are accessible is incredibly important. The simplest means of accomplishing this is by providing labels (via the <label> element, aria-label or aria-labelledby) for each of your inputs. Sadly, only 22.33% of pages provide labels for all their form inputs, meaning 4 out of every 5 pages have forms that may be very difficult to fill out.

Indicators of required and invalid fields

When we come across a field with a big red asterisk next to it, we know it’s a required field. Or when we hit submit and are informed there were invalid inputs, anything highlighted in a different color needs to be corrected and then resubmitted. However, people with low or no vision cannot rely on these visual cues, which is why the HTML input attributes required, aria-required, and aria-invalid are so important. They provide screen readers with the equivalent of red asterisks and red highlighted fields. As a nice bonus, when you inform browsers what fields are required, they’ll validate parts of your forms for you. No JavaScript required.

Of pages using forms, 21.73% use required or aria-required when marking up required fields. Only one in every five sites make use of this. This is a simple step to make your site accessible, and unlocks helpful browser features for all users.

We also found 3.52% of sites with forms make use of aria-invalid. However, since many forms only make use of this field once incorrect information is submitted, we could not ascertain the true percentage of sites using this markup.

Duplicate IDs

IDs can be used in HTML to link two elements together. For example, the <label> element works this way. You specify the ID of the input field this label is describing and the browser links them together. The result? Users can now click on this label to focus on the input field, and screen readers will use this label as the description.

Unfortunately, 34.62% of sites have duplicate IDs, which means on many sites the ID specified by the user could refer to multiple different inputs. So when a user clicks on the label to select a field, they may end up selecting something different than they intended. As you might imagine, this could have negative consequences in something like a shopping cart.

This issue is even more pronounced for screen readers because their users may not be able to visually double check what is selected. Plus, many ARIA attributes, such as aria-describedby and aria-labelledby, work similarly to the label element detailed above. So to make your site accessible, removing all duplicate IDs is a good first step.

Conclusion

People with disabilities are not the only ones with accessibility needs. For example, anyone who has suffered a temporary wrist injury has experienced the difficulty of tapping small tap targets. Eyesight often diminishes with age, making text written in small fonts challenging to read. Finger dexterity is not the same across age demographics, making tapping interactive controls or swiping through content on mobile websites more difficult for a sizable percentage of users.

Similarly, assistive software is not only geared towards people with disabilities but for improving the day to day experience of everyone:

- The recent popularity of voice assistance, both on mobile devices and in the home, has demonstrated that controlling a computing device using voice commands is both desirable and essential for many users. Voice commands like these used to only be an accessibility feature but are now turning into a mainstream product.

- Drivers would benefit from a screen reading feature that, while they keep their eyes on the road, reads long pieces of text like news stories aloud.

- Captions are enjoyed not only by people who cannot hear a video but also by people who want to watch a video in a loud restaurant or in a library.

Once a website is built, it’s often hard to retrofit accessibility on top of existing site structures and widgets. Accessibility isn’t something that can be easily sprinkled on afterwards, rather it needs to be part of the design and implementation process. Unfortunately, either through a lack of awareness or easy-to-use testing tools, many developers are not familiar with the needs of all their users and the requirements of the assistive software they use.

While not conclusive, our results indicate that the use of accessibility standards like ARIA and accessibility best practices (e.g., using alt text) are found on a sizable, but not substantial portion of the web. On the surface this is encouraging, but we suspect many of these positive trends are due to the popularity of certain UI frameworks. On one hand, this is disappointing because web developers cannot simply rely on UI frameworks to inject their sites with accessibility support. On the other hand though, it’s encouraging to see how large of an effect UI frameworks could have on the accessibility of the web.

The next frontier, in our opinion, is making widgets which are available through UI frameworks more accessible. Since many complex widgets used in the wild (e.g., calendar pickers) are sourced from a UI library, it would be great for these widgets to be accessible out of the box. We hope that when we collect our results next time, the usage of more properly implemented complex ARIA roles is on the rise—signifying more complex widgets have also been made accessible. In addition, we hope to see more accessible media, like images and video, so all users can enjoy the richness of the web.